Environment and Trade 2.0

To focus political energy, governments and stakeholders from both the environment and trade communities should seize the ongoing discussions on WTO reform to integrate a stronger environmental dimension into the organization’s future, establishing an agenda for Environment and Trade 2.0, argues Carolyn Deere Birkbeck.

A crane lowers loads bags of rice into a cargo ship for export to Japan at the Port of West Sacramento in California, US, Image: Ken James, Bloomberg via Getty Images.

The global trading system is facing its worst crisis in 70 years. Amidst the re-emergence of tariff wars, paralysis at the World Trade Organization (WTO) and rapidly evolving trade dynamics, policymakers and experts alike are grappling with what the 21st century global trade agenda should be and how to advance it.

It is also a critical time for our shared global environment. The climate crisis, biodiversity loss, desertification, unsustainable natural resource use and air, land and ocean pollution: the scientific evidence underscores that ‘business as usual’ is not tenable. Stronger environmental performance is needed not only because of the breadth, intensity and urgency of the world’s environmental challenges but also because livelihoods, food security and human health are at stake as well. Inaction is already generating enormous externalities in terms of economic costs across the world, especially for the world’s poorest people.

The groundswell of support for a greener global economy reinforces the need for environmental and social considerations to be central to economic policymaking. New business opportunities linked to a more sustainable global economy are estimated to reach US$12 trillion or more by 2030.1 A growing number of pioneer companies increasingly view 'sustainability' as not only necessary but as a source of competitive advantage and profitability, and are adjusting their business models accordingly, including by investing in more sustainable products and more sustainable sourcing in their global value chains. In addition, many governments are taking note that a greener economy could boost employment through green jobs that revitalize ailing economic sectors and regions, while aiding progress on development, inclusiveness and poverty reduction.

More than 30 years since public concerns propelled ‘environment and trade’ into the political spotlight, however, both the current agenda and political engagement lag behind the need for urgent action on an array of environmental challenges. Despite areas of considerable progress, the environment and trade agenda is out of step with the dynamism of the ‘willing world’ of governments, businesses and citizens committed to economic transformation in favour of sustainability.2

To promote a global trading system that proactively supports a more sustainable global economy, there needs to be focused attention on what an updated and transformative environment and trade agenda 2.0 could look like and, critically, how politically to advance it.

What is missing from the current policy agenda and how does it need updating? How can we draw together a vibrant but dispersed array of trade and environment initiatives into a compelling agenda that is greater than the sum of its parts? How can we can translate the growing political awareness, that making trade work for the environment is vital, into concrete decisions and action? More ambitiously, what is required to move beyond the accommodation of environmental concerns toward the deeper economic transformations that sustainability demands? And, strategically, what role could a stronger environmental agenda play in restoring multilateralism in trade?

To focus political energy, governments and stakeholders from both the environment and trade communities should seize the ongoing discussions on WTO reform to integrate a stronger environmental dimension into the organization’s future. Specifically, they should target the 2020 WTO Ministerial Conference as an opportunity to galvanise the political engagement of a critical mass of countries around reviving and upgrading the WTO’s environment agenda.

Importantly, there is growing political momentum. As the Brazilian Amazon burned, the link between climate action and trade policy was a top agenda item at the G7’s annual summit in August 2019, with several governments arguing that trade deals must be contingent on implementation of the Paris accords. Alarmed at the rapid acceleration of deforestation in Brazil, Austria, France and Ireland have declared they will not ratify the recently concluded EU-Mercosur Trade Agreement – the EU’s biggest trade deal to date. In September 2019, a central focus of the UN’s Climate Action Summit was on the need to end fossil fuel subsidies – an issue where the WTO is uniquely positioned to provide a forum for negotiations on new international disciplines.

A worker removes a tarp cover bales of compressed plastic waste on a truck in Gimpo, South Korea following bans on some plastic waste imports to China. Image: Jean Chung/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Furthermore, on the high-profile issue of marine plastic pollution, China’s 2018 import ban on certain types of plastic waste not only transformed trade flows in plastic waste, it has demonstrated the potential of China to energize discussions on environment and trade, including on the role the WTO could play in tackling plastics pollution. Also at the UN Climate Action Summit, Costa Rica, Fiji, Iceland, New Zealand and Norway announced their intention to launch negotiations on an Agreement on Climate Change, Trade and Sustainability in early 2020.3

The moment is now for the environment and trade communities alike to re-engage politically on improving the sustainability of the global trading system.

Integrating the future of trade and the global environment

Over the past 30 years, the trade-environment debate has matured enormously: the range of issues under discussion has expanded, stakeholder engagement and expertise have grown and the priorities, strategies and diversity of actors have evolved considerably. While views vary by issue, most developing countries are more open to discussion of environment-trade intersections than they were three decades ago. Indeed, on issues such as fisheries and fossil fuel subsidies, some developing countries are key players in demanding action at the environment-trade interface.

There is now little dispute that international trade flows, rules and policies are directly and deeply relevant to environmental performance. On the one hand, environmental considerations and requirements can constrain the commercial prospects and competitiveness of some players. Absent effective environmental management over trade flows, rules and policies, on the other hand, can exacerbate environmental challenges. In a globalized economy, consumers regularly purchase goods produced or disposed of in unsustainable ways in other countries, therefore ‘exporting’ environmental costs.

Trade rules and flows can also be harnessed to support environmental agendas and there are vast commercial opportunities on the environmental front. Global trade in environmental technologies is, for instance, projected to reach US$2-3 trillion by 2020.

At the global level, the leaders of the WTO and UN Environment argue that greater coherence between trade and environmental policymaking is vital for boosting sustainable trade, for promoting innovation and markets in sustainable goods, services, technologies and business models and for securing ‘win-win’ solutions where trade policy rules can be harnessed to advance environmental goals.

And there have been important political signals form both organisations. In 2018, the heads of the WTO and UN Environment launched a new initiative to strengthen their collaboration on environment and trade, and to facilitate dialogue among all stakeholders.4 5 In Davos, they also joined 11 high-level government representatives to create the Friends Advancing Sustainable Trade. Meanwhile, along with an array of senior trade officials, they regularly highlight the role that trade must play in advancing progress on the UN’s 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which include numerous trade-related goals, targets and indicators. Indeed, the SDGs highlight trade as a central and cost effective6 ‘means of implementation’ of the UN 2030 Agenda as a whole.

Rulings on WTO trade and environment disputes over the past decades have affirmed that trade rules do not prevent governments from adopting and enforcing carefully crafted environmental measures that respect core trade principles such as non-discrimination. Debate on the legal questions that previously dominated environment and trade discussions has now given way to a focus on specific problems, such as like fisheries subsidies. At the regional, bilateral and plurilateral level, trade agreements not only widely replicate the set of core environmental provisions present in WTO agreements, they also include a diversity of additional environmental provisions and innovations. The environmental provisions and sustainable development chapters in the 2016 Canada-EU Trade Agreement and the 2019 EU-Mercosur Trade Agreement, for instance, highlight the steady evolution of efforts to address trade and environmental intersections and the expanding set of possibilities.

Furthermore, environment and trade issues have also been taken up by an expanding landscape of international rules, processes and organizations – including on illegal wildlife trade, trade in hazardous waste at the Basel Convention and trade and sustainable agriculture in the Food and Agriculture Organization.

On the ground, there has been a proliferation of practical trade-environment efforts from a growing range of business and civil society groups including public-private partnerships, corporate social responsibility initiatives and voluntary standards and labels on a broadening array of sustainability criteria. The Trade for Sustainable Development community is actively working to galvanize and support businesses of the future to invest in more sustainable global value chains and greener exports, and respond to growing consumer interest in how sustainably products are produced.

But all is not well

Despite all of the above, most trade policymakers are far from politically embracing the idea that trade is a vehicle through which sustainability can be actively promoted. Sustainability concerns are rarely central to the heart of commercial bargaining; they remain a secondary, side issue for most trade negotiators.

Compared to the bubbling of activity on the sustainability-economy interface in the global policy arena – on decarbonization, the circular economy, the green economy, green finance, sustainable industry, sustainable infrastructure and sustainable transport – the trade-environment agenda seems especially stale. Whereas leading finance ministers and central bank leaders – hardly previously known for their environmental activism – are now actively promoting action on climate change, unfortunately most trade ministers are far less politically engaged.

On the substance, the environment-trade agenda has become increasingly complex, dispersed and specialized. Vexed environment-trade issues remain unresolved – and in some cases barely discussed at all. The WTO’s Trade and Environment Committee has long had a broad work programme with a set of critical environment and trade issues for discussion – from environmental labeling to environmental taxes. However, the existing CTE agenda was adopted almost 30 years ago. Although the topics on its agenda are still important and relevant, they are not framed in a way that resonates with the national environmental ministries or stakeholders, whose engagement will be vital to moving issues forward. Furthermore, while the long-standing work programme has proven flexible enough to accommodate traditional' as well as some 'new' environmental issues, it does not grant the most critical and contentious contemporary environment and trade issues – like climate – the scope for political attention and dialogue they merit.

Faced with competitiveness concerns, governments continue to spar about how to share the economic costs of environmental action (and of failures to act) and about the extent to which trade rules should be put at the service of environmental goals. Underpinning these debates are a set of longstanding trade-environment tensions: most centrally related to apprehensions that environmental measures and sustainability requirements can disguise protectionism, distort trade and limit market access particularly for developing countries keen to boost value-added production and exports and to diversify their economies.

Buyers inspecting tuna at the tuna market in Katsuura on the Kii Peninsula, the premium tuna auction in Japan. Image: Leisa Tyler/LightRocket via Getty Images

Admist these challenges, the key word routinely voiced by trade negotiators is ‘caution.’ The failure of enough governments to harness the political energy, focus and determination to find solutions to many pressing trade and environment issues – while no doubt technically and politically complex – has real and immediate environmental and economic costs. Despite the WTO’s efforts to portray negotiations on fisheries subsidies as a signal of its environmental credentials, 19 years of talks have thus far yielded nothing concrete in what should properly be considered a stunning failure. Negotiations at the WTO on environmental goods have stalled. Meanwhile, trade policymakers routinely sidestep systemic trade-environment issues – such as the scale effects of trade in terms of impacts on climate, biodiversity and ecosystem health – as ‘too hard’.

In the 21st century global economy, traditional approaches to categorizing and dividing attention to trade issues (such as through separate agreements on rules, government procurement, agriculture and services) are ill-suited to how products are actually produced and traded. On trade-environment issues, too, few issues fit neatly within such silos. Most trade-environment topics are multi-dimensional: they are relevant to more than one set of trade rules, overlap with other trade-environment challenges and have development dimensions – all of which are difficult to address in the context of long-established and rigid silos of trade agreements, negotiating sessions and committees.

The need for integrated international policymaking has never been greater. The holistic approach needed to address the nexus of challenges related to trade, climate, energy, agriculture, deforestation, and food security is difficult to advance, however, within current institutional and legal frameworks. A key stumbling block to more coherent international frameworks is that, at the national level, too few governments rise above bureaucratic silos to integrate environmental and trade policymaking.

Looking forward, discussions of environment and trade must grapple with ongoing changes in what is traded, and among whom, as well as 21st century economic realities in the trade arena and their environmental implications. These include the following:7 8 9 10 11

Changes in where ‘trade action’ takes place. The rise of the share of world trade among developing countries in terms of exports and imports, the increasingly dominant role played by China and other Asian countries and the growth of South-South trade is associated with a shift toward regional trade integration and regional intensity in global supply chains – especially for trade in goods.

Changes in what is traded. Trade in services – such as transportation, communication and business services – is among the fastest growing components of world trade – far outpacing trade in manufactured goods. By transforming trends in domestic production and output, growing services trade presents a diverse range of poorly studied challenges and opportunities for the environment.

Changes in how trade happens. The integration of supply and production networks as well as the rise of the digital economy are changing how goods and services are produced and delivered around the world. Global value chains for products now combine goods, services, investment, intellectual property and know how and they fuel the growing importance of services – such as logistics, shipping and airfreight and maintenance and repair. Intra-company trade accounts for around one-third of global trade.

Digitalization and the ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’. The growth of the Internet, e-commerce and the digital economy and the rise of new technologies from 3D printing to artificial intelligence and blockchain are not only changing where and how products and services are produced – and the distribution of associated environmental impacts – it also offers new tools and technologies, such as with regard to production processes and traceability of products, that could assist in greening value chains.

Scientific advances. Rapid scientific advances are expanding the range of goods and services that are traded globally and the ways they are produced. Artificial intelligence, biotechnology, nanotechnology, gene editing, materials innovation and biomimicry, for example, prompt questions about the relevance of trade rules and environmental implications.

Growing intertwining of trade, investment and finance. Responses to many environmental challenges demand more coherent approaches to international regulation in each of these areas.

Lack of coherent policy frameworks. Finally, while the growing array of practical initiatives to boost sustainable trade – from sustainability standards to green labelling – signal the potential for change, they lack the wider trade policy frameworks to help them scale up and to address legitimate competitiveness and transparency concerns.

A forward looking agenda

Amidst efforts to advance implementation of the UN SDGs, there is an urgent need for political leaders to re-engage on environment and trade issues. To inspire their attention, and demonstrate the opportunity to achieve real and important outcomes – both for trade and for the environment – we need an environment and trade agenda 2.0 – one that aims at fostering transformative change toward a more sustainable economy. In addition to leadership from the trade community, moving this agenda forward will also demand re-engagement from the international environmental community.

This refreshed agenda should not be limited to one organization but should be taken up in a cooperative spirit by the range of relevant international processes, including the forthcoming 2020 WTO Ministerial Conference, the annual meetings of the G7 and the G20, UNCTAD’s Trade and Development Conference in 2020, the UN Environment Assembly in 2021 and the OECD’s annual Ministerial Council meeting. The 30th anniversary of the Rio Declaration in 2022 and the half-way point of the UN’s 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda in 2023 are additional targets for galvanising political action.

Learning from the past, an environment and trade agenda 2.0 must be inclusive and based on informed engagement by the diversity of stakeholders at the national and international level. It must address development and competitiveness concerns, as well as the costs of environmental degradation, the economic fall-out from which is predominantly borne by the world’s poorest people.

Critically, an environment and trade agenda 2.0 must be able to attract and retain the political engagement of developing countries. Already, changing economic opportunities in global value chains, growing awareness of the economic potential of greener exports, and capacity building to meet higher environmental standards are spurring many developing countries to actively favour sustainable trade. The challenge is to translate this awareness into engagement at the international level to promote an environment and trade agenda that reflects wider sustainable development concerns. As noted above, several developing countries are active on calls for new WTO disciplines on fisheries and fossil fuels subsidies. In this vein, Costa Rica was a leading force for the creation of the Friends of Sustainable Trade and China will clearly be a vitally important player with regard to the future of the trade-environment agenda. In Africa, Ghana is leading by example on promoting a more circular economy, and on dialogue on the trade dimensions of promoting greater circularity in global value chains.

An updated trade and environment agenda 2.0 must do the following:

-

Promote system-wide efforts that harness and upgrade the range of the global trading system’s functions to boost attention to environmental priorities – from rule-making and dispute settlement to transparency, monitoring, information exchange and data collection, policy dialogue, assessment, capacity building, technical assistance and training.

-

Move beyond silos embedded in existing trade rules and mechanistic approaches to explore new ways to address the complexity and intersection of multiple environmental and trade challenges.

-

Embrace a diversity of approaches from top-down negotiation of international trade rules to voluntary initiatives and public-private partnerships – and be designed to bridge efforts across these difference governance approaches.

-

Harness non-trade instruments – such as multilateral environmental agreements that incorporate trade-related environmental measures – as a critical part of the trade-environment governance system along with the burgeoning array of practical initiatives, standards and partnerships designed to boost sustainable trade.

-

Promote efforts at all levels – multilateral, regional, bilateral and plurilateral level – particularly given the growing regional intensity of trade and the fact that their environmental provisions already go well beyond those found at the multilateral level.

-

Explore new institutional approaches to cooperation among international organizations, processes, initiatives and stakeholder efforts to promote coherence around shared sustainability goals.

-

Spur greater consultation and dialogue within national governments in favour of policy frameworks that better integrate the concerns of trade ministries with the environment-related priorities of other ministries (such as those responsible for environment and natural resources, development and industrialisation, agriculture, and health).

Advancing environment and trade at the WTO: a proposal for action

To realize the potential for trade as a means of implementation of the SDGs, WTO members should consider how to re-tool and harness the multilateral trading system to better serve sustainable development – as called for in the Preamble to the 1994 WTO Agreements – and to revive multilateral leadership on trade and the environment.

What can be done at the WTO to support a greener global economy and to help scale-up efforts to make trade more sustainable? How can we make the whole of the organisation’s work on environmental matters greater that than the sum of its many parts?12

To inspire political leadership on environment and trade by a sufficiently large coalition of WTO members, we need an agenda that builds on what is already on the table and that is not overly complex. From the long laundry list of environment-trade challenges and intersections, strategic priorities are needed, with a focus on those that can appeal to the environmental and economic interests of developing countries.

A trade and environment agenda that has the potential to galvanize political support is one that is system wide. The goal here is not, for instance, to simply update the work programme of the WTO Committee on Trade and Environment, if for no other reason than environment issues appear across the work of the WTO’s regular committees, in numerous negotiations, and in many of its activities. Nor should a forward-looking agenda be seen as one limited to negotiations for new market access or disciplines. While both of these are vital, an Environment and Trade Agenda 2.0 is one that provides a path forward and harnesses each of functions in the WTO’s tool kit. New approaches such as voluntary commitments on environment and trade, supported by greener aid for trade should also be considered.

Specific topics for an environment and agenda 2.0 at the WTO could include:

1. Launching, reframing and completing sustainability-focused negotiations including:

- Completing negotiations for meaningful disciplines on fisheries subsidies;

- Relaunching negotiations on environmental goods and services;

- Launching negotiations for disciplines on fossil-fuel subsidies;

- Reframing and re-energizing agricultural negotiations to focus on sustainable agriculture.

2. Initiatives, including:

- Launching a WTO Initiative on Climate and Trade that would, in addition to action on fossil fuel subsidies, include dialogue, research and information-exchange on carbon pricing; liberalisation of climate-friendly technologies, goods and services; transportation; and climate-related standards and labelling;

- Launching a WTO Initiative on Plastic Pollution and Trade, which could harness each of the elements of the WTO’s tool kit – transparency and information-exchange on trade-related measures and sustainability standards; research on trade flows and global value chains across the life cycle of plastics; cooperation with other international organisations; and potentially targets and voluntary commitments for reductions in trade of certain types of plastic.

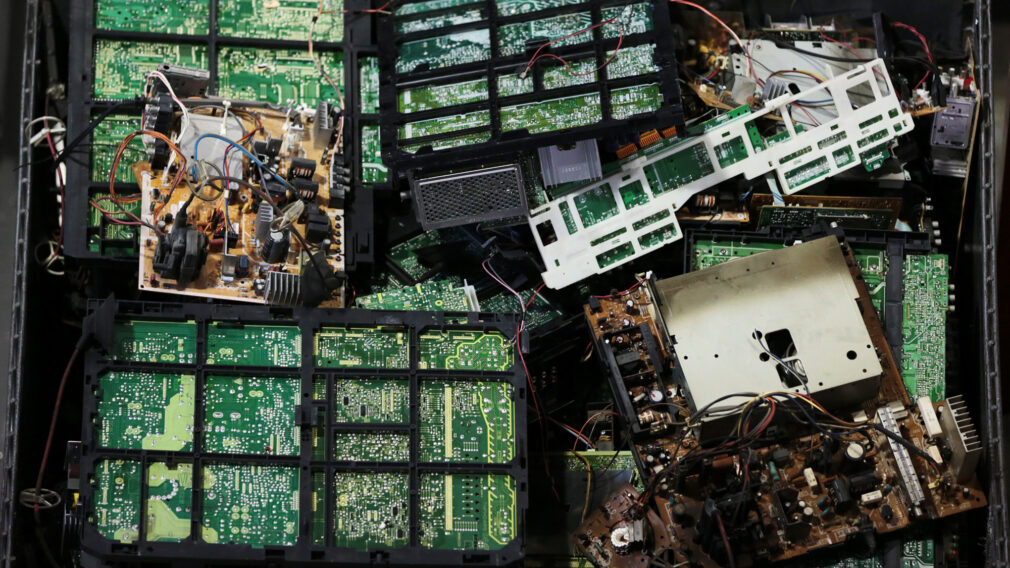

Motherboards removed from dismantled televisions are sorted for recycling at the Panasonic Eco Technology Center (PETEC) plant in Japan. Image: Yuriko Nakao, Bloomberg via Getty Images.

3. Multi-stakeholder policy dialogues, including on:

- Trade policy frameworks for paradigm shifts in favour of a more circular economy, consumption-based ecological accounting and green new deals;

- Sustainability standards and sustainable value chains, including the potential to harness ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’ trends to trace, optimize and bring transparency to environmental dimensions across value chains.

4. Research, assessment, information exchange and monitoring, including on:

- Each of the topics outlined for new initiatives and policy dialogue above;

- The role of trade agreements and measures with regard to the implementation of multilateral environmental agreements;

- The scale effects of trade on biodiversity and ecosystem health and ways to address them.

5. A work programme for Greening Aid for Trade, including:

- Boosted financial support for the range of practical initiatives undertaken by other international organisations to promote opportunities for developing countries in more sustainable trade and in adapting to sustainability standards in global value chains and export markets.

An immediate opportunity is to harness ongoing debates on WTO reform and the forthcoming 2020 WTO Ministerial Conference to signal renewed high-level commitment to environment and trade matters. A Ministerial Statement on environment and trade would send a firm signal that Members understand the importance of ensuring the WTO does its part to promote a greener global economy and could set out a clear forward-looking agenda, that builds on its existing work programme but adds vital new dimensions, backed by political commitment.

Rather than presenting yet another set of challenges for an already beleaguered WTO, an environment and trade agenda 2.0 could actually be a catalyst to restore its relevance. Making trade and trade policy part of the answer to the environmental challenges that are clearly facing us – rather than trying to avoid them – could be key to restoring or remobilizing that support. Thinking bigger on environment and trade front may help garner a critical mass of political support for the multilateral trading system within key countries, both from growing environmental constituencies and also from businesses keen to advance a more sustainable economy, but in need of a transparent, coherent and stable global policy environment.

The current political climate and uncertainty at the WTO should not deter governments from exploring what is possible. As the WTO struggles to reassert its relevance and role, a clear signal of engagement on a greener global economy could be a vital lifeline. Governments and stakeholders alike should re-engage now to strategize on concrete next steps to move a revived agenda forward.