COP26: A Roadmap for Success

The next 14 months are critical in the fight against climate change. Ahead of the 26th Conference of the Parties in Glasgow in 2020, this article proposes a roadmap for a successful UK presidency that will deliver greenhouse gas reduction commitments at the level needed to avoid dangerous levels of climate change.

Glasgow Riverside Museum Of Transport. Image: View Pictures/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

The COP26 challenge

The United Kingdom will host the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP261) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Glasgow at the end of 2020 and the next 14 months leading up to this event will be decisive in the fight against climate change.

In 2015, 196 countries adopted the Paris Agreement with the core objective of keeping the global average temperature rise to below 2C above pre-industrial levels while pursuing efforts to keep it to below 1.5C. Recognizing that the commitments made at the time were insufficient to meet that goal, these countries also agreed to present revised and more ambitious commitments by 2020 and every five years thereafter. COP26 sets a deadline for countries to present this first revision, and as such, will be a determining moment for global climate action.

If COP26 were to be a failure – or just a diplomatic success allowing the UN process and the UK presidency to save face without significantly increasing the level of ambition to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions or for adaptation and finance – it would become impossible to limit the average rise in temperatures to below 2C and even less so to 1.5C.

The recent IPCC Special Report on 1.5C all too vividly depicts the dire consequences of global warming beyond 1.5C – for the environment, the economy and people. The stakes for COP26 could hardly be higher and the challenges ahead are equally consequent.

According to the United Nations Environment Programme’s 2018 Emissions Gap Report, global GHG emissions should not exceed 40 Gt (billion tons) of CO2-equivalent in 2030 if the world is to limit the average rise in temperatures to below 2C – and 24 Gt to limit it to 1.5C.2 By way of comparison, fully meeting the commitments made in Paris at COP21 in terms of GHG emission reductions and finance would only reduce the level of emissions in 2030 – based on current trajectory with measures already implemented to be upheld – from 59 Gt to 53 Gt.3

In other words, limiting the average temperature increase to well below 2C implies multiplying the level of ambition of current reduction targets for 2030 by a factor of three – and by a factor of six to limit it to 1.5C.

The tension between science and politics

Given the scale and speed of the socio-economic transformation that is required to meet the required levels of ambition, there is an inevitable tension between what is scientifically necessary bin the long run and what is considered politically feasible in the short term.

A real stepping up of ambition will be necessary ahead of COP26, however, the meeting will not be – and should not be portrayed as – the point in time when climate change will be solved once and for all or when the 2030 GHG emission gap will be closed entirely.

Learning from previous COPs

The lessons learned from COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009 – when expectations were set at a level that was unrealistic in addition to being widely divergent between different groups of countries, NGOs and businesses – should be remembered and taken seriously. The failure to reach a global climate deal in Copenhagen – after which the UN process had to be rescued in Cancún in 2010 and a new mandate for a global climate deal negotiated in Durban in 2012 before it was finally adopted in Paris in 2015 – resulted in six years of global climate efforts that were too slow and too little compared to the urgency needed to tackle the changing climate.

As the authors of this paper were personally involved in the negotiation of the Paris Agreement in 2015,4they also hope that some lessons can be learned from the process that led to its successful adoption at COP21 even though the objectives – and the context – for COP26 are profoundly different.

The objectives for COP26

Setting the expectations for COP26 will be a key starting point for a successful presidency. Situating COP26 as a key moment for climate action, the presidency will have to set a highly ambitious goal and go, not one, but many steps beyond what has been done so far. Recent scientific reports have made it clearer than ever that small steps are no longer sufficient. Climate change is no longer a distant threat for future generations but the defining challenge for current ones. While limiting the average rise in temperatures to 1.5C is still technically feasible, the window of opportunity for doing so is closing fast.

Because so many actors are involved in the climate regime, and there is no centralized governance mechanism, designing a plan and sharing it far ahead of the COP is the best way to increase convergence and shape expectations.

This plan should be deployed around four strands of action. The first is to mainstream the objective of net zero emissions and carbon neutrality by 2050, or very soon after, as the basis for every action. The second is to organize pressure for every country to increase its national contributions for 2030 and to call on businesses and local governments to present their commitments for 2030 consistent with the long-term objective. This new parallelism – and harmonization – between governments and non-state actors will reinforce and bring clarity and credibility to climate action. The third strand is to respond to the emergency of the climate crisis by deploying concrete and rapid responses consistent with the objectives. The fourth is to set up an organized and consistent finance plan providing real leverage between the different financial actors.

Positive dynamics to rely on

The challenge is considerable, but several positive dynamics have been set in motion since COP21.

Carbon neutrality: the concept of carbon neutrality – meaning zero net emissions – is progressively establishing itself as the only long-term objective (i.e. around 2050) consistent with the Paris Agreement for all countries and sectors. As the first advanced economy to legislate a net zero 2050 target, the United Kingdom is well positioned to build on momentum in this area and establish its legacy at COP26.

Sectoral decarbonization: Different sectors are undergoing profound changes and moving towards decarbonization albeit too slowly and unevenly depending on geographies for instance in:

Citizen mobilization: Citizen mobilization around climate issues, especially in developed countries and led by young people, is growing stronger and starting to spill over into some developing countries. In the face of more regular and serious impacts, for example, extreme temperatures, floods and heatwaves, the view of climate change is growing as an urgent social and generational issue in which all political parties are now forced to take an interest. Political ecology is reaching beyond its traditional electorate and support for action to respond to the climate emergency is attracting broad popular support from voters across the political spectrum. The recent European Parliament elections, for instance, showed that many citizens now see climate change as a key political priority.

Tens of thousands took to the streets in Central London taking part in the Global Climate Strike, September 20th 2019, United Kingdom. Image: Kristian Buus/In Pictures via Getty Images.

Challenges ahead

Despite these encouraging aspects, the following challenges remain. COP26 does not at this stage present itself as the major political event it will need to be. In preparation of his climate summit in September, UN Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, has made precise and systematic requests to countries to raise their commitments in line with the Paris Agreement objectives.5

The UN system currently does not support Guterres’s demands, in fact sometimes it opposes them, while few countries are responding to them. It is urgent for heads of state and government committed to climate action therefore, including the UK prime minister, to express clear political support for the UN secretary general’s demands and to ensure that they are pursued in the lead up to COP26. These can of course be amended and completed with further demands, for example, on nature-based solutions and biodiversity which the UK prime minister has flagged as a key issue for COP26.

Ensuring key players lead the way

The United Kingdom, as host of COP26, and the European Union should lead by example by taking bold climate action. The latest European Council conclusions in June 2019 demoted the objective of carbon neutrality by 2050 to a bottom-of-the-page mention and failed to mention anything about raising European ambition for 2030. This does not place the EU in a leadership position let alone one in which to exert credible or effective pressure on other countries. It is essential that these conclusions be reviewed and corrected as soon as possible as it would be an important political tool in the ambition sequence leading to a successful COP26. European Commission President-elect, Ursula von der Leyen, has committed to legislate on the objective6 and coordinated action between progressive countries in Europe – including Germany – that have committed to net zero emissions by 2050 could help von der Leyen deliver a necessary increase of EU contributions and encourage lagging countries to adopt the net zero objective too. The United Kingdom on its own will have to do the same.

However, even raising the EU 2030 target to 55 per cent of CO2 emissions would only deliver around 0.75 Gt which is very little compared to the scale of the projected global gap. By way of comparison, recent analysis found that China’s CO2 emissions could peak before 2025 and bring a reduction of 2 Gt to 4 Gt CO2 by 2030, for a 2C scenario and 1.5C scenario respectively, compared to an enhanced low-carbon scenario.7 It will therefore be key for the United Kingdom and others to boldly reduce GHG emissions themselves and to use this to put pressure on big GHG emitters as part of a reciprocal approach of accelerating action.

Ensuring big GHG emitters to close the gap

China, India, South Africa, Indonesia and Vietnam are preparing to increase their commitments in 2020 unlike Brazil and Mexico. However, their approach remains incremental with some of them simply presenting how their current climate policies could enable them to exceed their existing 2020 and 2030 nationally determined contributions targets presented in 2015, which were for most of them, close to the business-as-usual trend.

A motorcyclist travels along a road as smoke rises from a chimney at the Tata Power Co. Trombay Thermal Power Station in Mumbai, India. Image: Dhiraj Singh/Bloomberg via Getty Images.

Clear and precise objectives could be set here such as raising the objective of the share of non-fossil fuel sources in primary energy consumption including other GHGs as part of emissions-reductions objectives, reducing carbon intensity overall or including new sectors such as transport or agriculture. As it is the biggest emitter, putting pressure on China to pursue these objectives to address its own emissions and those related to international projects, such as its Belt and Road Initiative, will be key in the lead up to COP26.

Moreover, the key political milestone for China is the completion of its 14th five-year plan (2020-25). The objectives of this plan are a make-or-break element for the future of global emissions. Concerns about the trade war between China and the United States and a slowdown of economic growth may deviate the Chinese plan from its ambitious targets on coal, the electrification of transport or renewable-energy deployment. That is why the dialogue between Europe and China is particularly important in this final phase of the plan’s design – to give some certainty about the global trajectory. By the same token, making the case for green projects through dialogue and joint projects on the Belt and Road Initiative could improve the carbon footprint of Chinese foreign investment which is of a considerable scale.

Uncertainty about the US election results in 2020 will weigh heavily on COP26. Even in the case of a Democratic Party win, the United States will not be in a position to present anything more than a ‘shadow’ commitment at COP26 which will take place just a few days after the elections. The United States’ withdrawal from the Paris Agreement has been in part compensated by the mobilization of US states, cities, companies and investors. However, it continues to weigh heavily on political dynamics (e.g. see the G7 and G20) and also on the dynamics of fossil-fuel investments (e.g. see oil and gas).

In any case climate change will be a hot issue in the presidential, Senate and House campaigns in 2020 as many actors, including businesses, have and will continue to push for candidates to take this issue seriously and announce their actions. However, a new Republican Congress, and especially a second Trump administration, would make it more difficult to raise ambition among other key players internationally as it would raise concerns about the credibility of the multilateral process and the usefulness of engaging with it.

Working in a new and difficult geopolitical context

Overall, the presidency will face the challenge of working in a new geopolitical context in which climate action has become an unavoidable political issue but also a polarizing one – internationally and on a domestic level. The presidency will have to carry the message that responding to the climate crisis is necessary but also compatible with other economic and social priorities. In the context of the UNFCCC, this will mean finding the best compromise between the demands of the most vulnerable countries experiencing climate impacts more brutally and regularly than ever before and those of emerging economies wanting to protect their development needs.

Plan of action for a successful COP26 presidency

Since COP21, international climate action has suffered from a certain fragmentation and confusion. There is still no general framework through which to assess the multitude of actions ultimately seeking to limit the temperature rise to below 2C, and if possible, to 1.5C. There also is no comprehensive bilateral action plan to focus on key countries to encourage climate action and respond to specific demands.

We are entering a new phase. COP26, which will take place in Scotland in November or December 2020, sets a deadline for increasing national contributions. The UN secretary general’s climate summit in September 2019 is an important political event: it must be the opportunity for a group of leading countries – which the United Kingdom and the European Union should be part of – to make initial announcements. The requests made by the UN secretary general (e.g. see his letters sent to heads of states and governments) are clear and precise but they will need to be taken up by the Chilean and UK presidencies ahead of COP25 and COP26 as well as by other heads of states and governments in order to be effective.

The ‘four pillar’ structure of the Paris Agreement – the agreement itself, national contributions, funding and commitments of non-state actors – made the objectives of COP21 very clear, two years ahead of time, and mobilized a very large number of actors. The following action plan for the United Kingdom in the next 14 months could serve a similar function.

A. Carbon neutrality as a basis for climate action

In order to limit the temperature increase to any level, global GHG emissions must at some point reach zero. To limit this increase to below 2C, GHG emissions must reach zero in 2085, while to limit it to 1.5C, they must reach zero in 2070 (2050 for CO2 emissions only) and become negative beyond that date. In the Paris Agreement, countries are invited, but not obliged, to present their long-term low-GHG-emission and resilient-development strategy before 2020. To date, 12 have done so, including seven from the G20 and six from the G7. A number of cities, companies and investors have also published their strategies for achieving carbon neutrality.

Demands on carbon neutrality objectives could vary for different country groups:

- All OECD countries' strategies should include an objective of achieving carbon neutrality as early as possible and by 2050 at the latest.

- Most G20 countries’ strategies (including those of China, Russia, Turkey, South Africa, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia and Singapore) should at least articulate a carbon-neutrality trajectory, even if it is to be achieved after 2050, and a plan for realizing this trajectory.

- For those in the G20 and other upcoming high emitters (including India, Indonesia, Vietnam and Nigeria), it is important that these strategies set a peaking date for GHG emissions and provide for a rapid reduction of their emissions after the peak towards carbon neutrality.

- All sectors, companies, investors and cities should be encouraged to do the same, with a particular emphasis on the top 100 emitting companies responsible for over 70 per cent of global GHG emissions.

Setting a carbon-neutrality objective is not in itself sufficient but it is essential as a long-term objective on the basis of which shorter-term commitments and policy decisions are taken, in order to transform economies to be compatible with the Paris Agreement. It is also one of the few clear signals that investors and members of industry really pay attention to along with fiscal measures.

COP26 could be the moment where a decision by the COP urges all countries to undertake such strategies, or revise them in line with science, in order to feed into the global stock take in 2023 and creates a norm of each country committing to reaching carbon neutrality taking into account their respective circumstances.

B. Increasing national contributions and commitments from cities, companies and investors

To be consistent with the objectives set by the Paris Agreement, existing national contributions for 2030 should be increased by a factor of three to six. While this is probably out of reach, even if it is the discourse that scientists and some NGOs will rightly hold, the COP26 objective needs to be presented as a rapid acceleration of climate action – not a mere adjustment on the margins. The mobilization of all actors – state and non-state – is therefore more important than ever and they should be called upon to increase their own action and leveraging power on each other.

To this end, it is essential for the revision of national contributions to be based on a long-term low-GHG-emission and resilient-development strategy as well as to demonstrate that the upward revision of the 2030 targets sets the country on the path to carbon neutrality. The cost reductions for a large portfolio of low-carbon technologies, as well as the mobilization of citizens and the growing support of investors and members of industry for the climate agenda, must make it possible to re-open discussions to review objectives that have already been set or even to enshrine them in law as was recently done in the United Kingdom and France. Non-state actors should also ensure their commitments are compatible with longer-term objectives informed by the latest scientific information.

C. Concrete and rapid measures in all sectors

National contributions made at COP21 in 2015 suffer from the following four major shortcomings that should be addressed in this new phase of climate action.

- They have not always been translated into concrete action, transcribed into law and/or accompanied by a finance plan.

- They have mainly focused on the potential of GHG emission reductions in the power sector (i.e. nuclear, renewable energies, energy efficiency) without integrating future cost reductions and benefits (including social and health) related to investment in innovation and deployment or the links with biodiversity and nature-based solutions. Despite the focus on the power sector there has been too little focus on the outsized need for a rapid global exit from coal use.

- They have hardly affected other sectors with high GHG emissions and where solutions already exist, such as agriculture, transport, industry and heating. Contributions also mainly focused on CO2 emissions rather than short-lived climate forcers such as methane or aerosols.

- They exclude, by definition, the international aviation and maritime sectors.

Countries should therefore be encouraged to include all sectors that were not – or only partly – included in their 2015 national contributions in their revised contributions in 2020.

Tugboats berthing an oil tanker at Qingdao port in Qingdao in China's eastern Shandong province. Image: STR/AFP/Getty Images.

More specifically, discussions on GHG emission reductions in the international aviation and maritime sectors should also be relaunched within their respective fora (e.g. the International Civil Aviation Organization and the International Maritime Organization) and through more ad hoc initiatives by countries and companies ready to move forward especially in Europe. The commitment of Maersk, the world's leading shipping company, to achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 is creating a new dynamic. GHG emission reductions in the maritime and aviation sectors are also a possible avenue for dialogue with the government of Brazil, as well as trade and the agreement with Mercosur, as part of the compensation for the emissions of aviation or maritime transport may come from avoided deforestation in the Amazon at least in the short to medium term.

In light of the 'biodiversity COP' taking place in 2020, in China, there is an opportunity to seize a push for a ‘2020 nature package’ that would highlight existing nature-based climate solutions. A particular effort should notably be made towards the major agricultural and forestry countries – Australia, Canada, India, Argentina, Brazil, China and Indonesia.

GHG emission reductions must be accelerated in sectors already covered by existing national contributions, in particular, coal. The UN secretary general is right to say that, in order to be consistent with the objectives of the Paris Agreement, no new coal-fired power plant projects should be developed after 2020 and that existing power plants should be phased out.

New analysis from the International Energy Agency (IEA) shows that almost a third of the climate footprint of the global energy system comes from coal use alone. Both the IPCC and the IEA have been clear that there are no credible global scenarios for reaching climate safety (for scenarios of 1.5 or 2C warming limits) that do not involve a huge and rapid drop off in global coal use. As the IPCC report on 1.5C concluded, ‘the use of coal shows a steep reduction in all pathways and would be reduced to close to 0% (0–2%) of electricity.’8

The United Kingdom, with its commitment to a definitive coal phase-out by 2025, will be able to strengthen this point. But to be coherent, this phase-out will have to be followed by a gradual exit from oil and gas when they are not accompanied by adequate carbon capture and storage (CCS) capacities. Investment in CCS, whether direct or indirect, will have to be one of the other major achievements of COP26 as a key determinant for carbon neutrality.

D. Finance: supporting developing countries and redirecting all financial flows

The issue of financing the ecological transition is complex and suffers from fragmentation and confusion. This has prevented pressure from being exercised on all financial-sector actors that must align themselves with the objectives of the Paris Agreement. The following four necessary levels of action can be distinguished.

- The Green Climate Fund (GCF), whose role, while not always well understood, is essential politically given the importance that developing countries attach to it and in practice as some poor and vulnerable countries do not have access to other resources to finance this type of action. Re-capitalizing the GCF is scheduled to take place this year. The United Kingdom has recently doubled its contribution.

- The USD 100 billion in public and private funding must be mobilized by developed countries to support developing countries' actions to reduce GHG emissions and for adaptation. With the recapitalization of the GCF and the increase in climate funds from multilateral and bilateral development banks, this objective should be achievable, particularly when viewed for the opportunities it would create. It is estimated that USD6 billion is needed annually in incremental subsidies to achieve this objective. The calculation methodology, carried out by the OECD in preparation for COP21, will nevertheless have to be adjusted and representatives from developing countries involved in the process for it to be approved.

- Development banks, including national ones, have a key role to play in financing the ecological transition beyond the climate funds they host. To do this they must align all their activities and investments with the objectives of the Paris Agreement (i.e. the ongoing work of the multilateral development banks and the International Development Finance Club) as well as develop their leverage effect for private investments (i.e. develop the financial instruments and governance reforms that enable them to do so particularly through ambitious policies and securitization).

- Finally, all actors in the financial system (e.g. institutional investors, asset managers, insurers and banks) will need to integrate climate and carbon risks into their investment decisions in order to scale up the ecological transition. The four recommendations of the Task-Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD), which are currently voluntary, should be made mandatory. At this stage France is the only G20 country to have committed to turn these recommendations into law. Among priority countries to follow suit beyond the United Kingdom are Canada, Japan and China alongside the EU. The disclosure of climate and carbon risk by investors will also need to be accompanied by a legal framework to ensure that they actually engage in the decarbonization of their portfolios. The International Monetary Fund, which is currently limited to research on carbon pricing and climate-risk coverage for vulnerable countries, will need to integrate macroeconomic risks related to ecological transition into its financial-risk monitoring activities as should central banks.

Overall, COP26 will need to deliver a 'climate emergency package' including:

- National long-term development strategies for decarbonization aiming for carbon neutrality.

- Concrete and revised actions and commitments from national governments as well as from local authorities, businesses and investors going beyond the focus of the initial round of nationally determined contributions – improving energy efficiency, scaling-up renewable energies and electrifying light-duty vehicles – to address other large sources of GHG emissions including oil and gas, aviation, maritime and trucks, and agriculture, forestry and other nature-based climate solutions.

- Concrete and rapid measures in all sectors.

- Ambitious financial commitments to support developing countries and to redirect all financial flows.

Taken together, these revised commitments and enhanced actions will need to bring credibility to the fact that global GHG emissions are about to peak and that rapid and large-scale GHG emission reductions after that peak will achieve net-zero GHG emissions by the second-half of the century.

The role of the UK presidency of COP26

The United Kingdom will be better positioned to exert influence internationally if it can point to a comprehensive framework for delivering domestically which would act as a strong ‘proof point’ to its diplomatic effort. This will be especially important since, as the host of the 2020 summit, its own climate plan will inevitably come under greater international scrutiny than those of other countries.

The United Kingdom can point to considerable progress, made under successive governments of different political stripes in decarbonizing the power sector. The result has been a drop in UK emissions to a level not seen since the 1850s and the creation of a low-carbon and renewable-energy economy employing more than 200,000 people and worth £45 billion a year.910 This has been achieved primarily through a successful focus on offshore wind investment, and shifting electricity generation from coal to renewables, backed by a cross-party political commitment to a total coal exit by 2025.

This summer, with extraordinary levels of parliamentary support from all sides of the House of Commons, the United Kingdom legislated a binding new national target to reduce emissions to ‘net zero’ by 2050. To get on track to achieve this goal, it will be necessary to go substantially beyond the progress to date in cleaning up electricity generation.

The opportunity exists for the United Kingdom to close its ‘emissions gap’ with an approach that is focused on investment in modernizing transport, buildings and heating infrastructure to improve efficiency and greater use of cleaner technologies that would also help bring good jobs and prosperity back to the country’s towns and industrial heartlands. Sustaining a robust carbon price in the event of the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union Emissions Trading System (ETS) will also be necessary to offer certainty to clean-energy businesses and keep the coal phase-out on track. Investments in cleaner air and nature restoration would also deliver major advancements in quality of life for millions of people and public-health benefits that would create large savings for the National Health Service. Enshrining high environmental standards in the United Kingdom’s new trade deals would bolster the market for its low-carbon industries and crucially help to protect global nature sites like the Amazon rainforest which will be essential to reaching climate safety.

With the right levels of political leadership from across the UK government, progress can be delivered in each of the following areas over the next year:

Infrastructure investment: Large-scale trials of heat pumps and hydrogen technology would address emissions from heating homes and businesses as well as develop a new market for clean heating technologies. Directing support to upgrading the energy efficiency of homes and businesses would cut household energy bills, reduce fuel poverty and create jobs in every community. Pioneering CCS for industry could lead to large-scale job creation in the northeast of England, Scotland and the North Sea. Continued investment in new electric-vehicle charging infrastructure, with new support to rail electrification and bus service improvements, would speed the transition in the transport sector. Overall, ensuring that 1-2 per cent of GDP is invested in decarbonization would be in line with the advice of the Committee on Climate Change and similar advice from the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC). The forthcoming Comprehensive Spending Review (CSR) expected ahead of COP26 offers the opportunity to ensure a fair balance between public and private investment and to manage the transition sensitively.

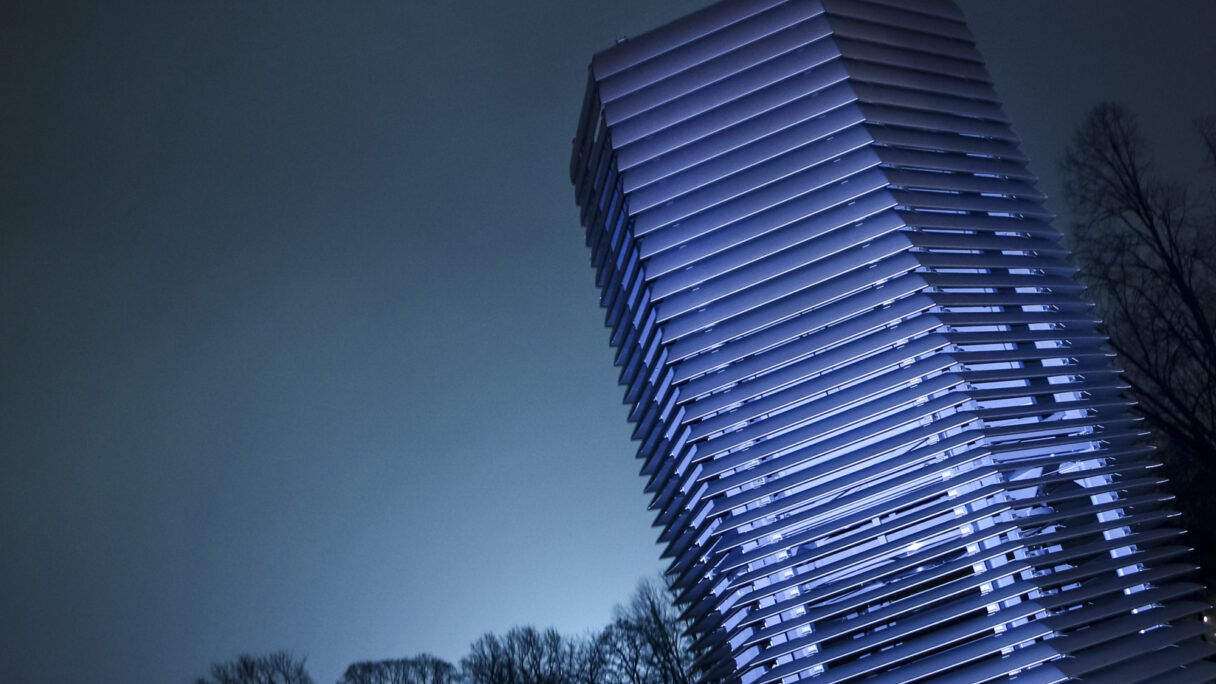

Smog Free Tower is showcased at Park Jordana in Krakow, Poland. The 7-meter tall structure is described as a smog vacuum cleaner. Image: Beata Zawrzel/NurPhoto via Getty Images.

Clean air: Forthcoming clean-air legislation may be the policy lever able to deliver the greatest emission reductions from road transport in the short term. The new clean-air legislation expected in 2020 offers the opportunity to address toxic air pollution from petrol and diesel vehicles which are causing 40,000 premature deaths a year. City mayors have outlined how £1.5 billion would enable the successful delivery of clean-air zones which would reduce the burden on the National Health Service.11 By 2035, the health and social care costs of air pollution in the United Kingdom have been forecast to reach up to £18.6 billion by leaders in the field.12 The Committee on Climate Change has been clear that 2040 is too late for the phase-out of petrol and diesel cars and vans and current plans for delivering this are too vague. The introduction of a zero-emission vehicle mandate for automakers, modelled on California’s successful approach, could offer a solution that would bolster the United Kingdom’s global leadership position in the manufacture and export of clean electric vehicles and drive down the cost for UK consumers of purchasing a new electric vehicle.

Nature-based solutions: Solutions to biodiversity loss and climate change are very often the same, for example, increasing forest cover and restoring peatlands. Brexit offers the United Kingdom opportunities to diverge from the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy. Linking public money to public goods, including carbon sequestration, in the land-use sector offers a significant short-term opportunity that would resonate in the rest of Europe and internationally. Forthcoming agriculture legislation could ensure UK agriculture no longer sits outside of climate regulations. Emissions from farming in the United Kingdom have not fallen for a decade and the Committee on Climate Change has suggested tree-planting rates should quadruple. Biomass in the power sector, which involves felling forests and importing woodchip for power generation, should no longer be considered zero-rated by the Treasury.13 Associated emissions should be covered by the carbon price.

Trade deals: Research by trade law experts at the University of Cambridge has identified the provisions that would enable any new trading agreements to assist in driving climate progress and be aligned with implementation of the Paris Agreement.14 Forthcoming legislation that will outline the process for post-Brexit trade deals should include opportunities for parliament to ensure new ones are stress-tested against sustainability criteria including the United Kingdom’s climate change objectives.